Welcome!

The inaugural letter of "In my Garden Grew..."

Dear Hayley and Jaclyn,

I am writing this first letter in your honor. You encouraged me to share my words and provided a safe space in which to do so. You have read countless drafts of myriad texts, caught innumerable convoluted phrases, pared down my superfluous use of poetic expressions, and exhorted me to continue. Our many conversations have refined my thinking and sharpened my writing. This venture would not be possible without your friendship, your practical support, and your constant encouragement to keep on writing. Thank you.

And now to my new readers.

Welcome!

The primary goal of In My Garden Grew… is to share my academic journey in a way that is intelligible and beneficial to those outside my field, hopefully sparking new thoughts, insight from a field you might not know very well, and maybe even a bit of encouragement. For myself, it challenges me to articulate what I think I know.

In this first letter, I will introduce the scope of this newsletter, my research, elements of my framework, a key value, and what you can expect. The current plan is to send two letters per month. One will be on an academic subject, the other will reflect my current ponderings and readings, and perhaps a poem now-and-again.

Scope

Each newsletter will be in an essay form and will focus on one primary topic. My intent, however, is to go beyond merely translating an academic article into lay terms. As I learn, I hope to share how the various threads interact and influence my thinking.

Research

On the academic front, the topics will include linguistics: a brief introduction to the field, then specifically Semitic linguistics1, and the language of the Hebrew Bible. I will consider how Hebrew linguistics relates to biblical studies and theology as I continue to wrestle with that question and work out my own hermeneutic.2 Cultural context issues have come to the fore in my own studies recently, and the cross-cultural (and cross-time) considerations are important as well. Means and methods of application hover constantly in the back of my mind. Further down the road, as I learn more about anthropology3 and the study of ontology4, I will share those reflections as well.

Framework

Along the way, various other threads of thinking may surface. I find the analogy of a tapestry to be helpful here: as a tapestry reveals and conceals its colors in a given scene, close inspection may hint at the underlying strands which contribute depth and shape. As the tapestry presents a story, so may my journey become apparent along the way. My perspective is that of a narrative, each individual scene a part of the whole. In this tapestry, the “scene” is my research project, and the “threads” are the many background pieces that influence the way that scene looks.

In order to have a scene, it needs a framework. Over the last few years of work on my Masters in Hebrew Language, my advisor went to great lengths to teach me the fundamental elements that need to make up the framework of my research. If the work itself is a tapestry, perhaps we can picture these as the supports that keep it aligned, framed and focused. Those supports, for my advisor, are humility, structure, and prioritization. In subsequent letters, I hope to share more of the value of structure and prioritization, but for now, let us consider humility; it has become an ever-present awareness as I write..

Humility

My advisor set humility as a foundation for working with him.

“You will finish this degree and you will be a master of the Hebrew Language. You will not know everything. But there are many things you will know. The challenge is to stand in the tension, aware of what you do know and what you do not know.”

Not a conversation or meeting passed without his eloquently reminding me of the essential place of intellectual humility in my work. Scientia potestas est—knowledge is power, so Thomas Hobbes famously plagiarized Sir Francis Bacon5—and its primacy in our Information Age lends itself to the reluctance of an admission of ignorance. As finite human beings, ignorance is woven into our being. Pretending otherwise is naive at the best, and arrogant at the worst. I’ve fallen into this particular pit many times.

It is a tension that requires deliberate attention, for we are liable to slip one way or another in any given moment. In my own experience, it is when I am most sure of my understanding that I fall into dangerous over-confidence. About half-way through writing my master’s thesis, I submitted a section for review. It was on a subject that I was well-versed in, and I was sure that I not only grasped the central elements but I’d expressed it with exquisite clarity. Additionally, I was confident it was my best writing yet. Going into the meeting with my advisor, I expected his praise and a quick review, and then we’d continue to the next section. His computer, I noted upon entering his office, did not have the document pulled up; I reminded him that I had sent it, but I could pull it up on my computer if he preferred. Instead, he sat back in his chair and proceeded to speak (again) on ways of knowing. My impatience grew and I silently opened the document while only partially listening to his soliloquy on epistemology. He ignored my frustration, and continued in his colloquial reflection on the dangers and benefits presented by both modernism and post-modernism. Finally, he drew me into the conversation as we veered into considering the representation of these philosophies in our context (contemporary Israeli history and society). When our time ran out, I was thoroughly engaged in the conversation, but then realized we’d not spoken at all about my research or the section I submitted. His response: “Keep writing, we’ll get to that next week.” I returned home, annoyed at the vagaries of professors, unsure of the point of our meeting. Then, I opened up the aforementioned section. With our conversation fresh in our memory, I looked at my words with a refreshed perspective—and immediate embarrassment. It is the most arrogant piece of writing I’ve ever been ashamed to call my own.

Humility, I continue to learn, takes work. It is more than adding in a few qualifiers to a sentence. While qualifiers are part of writing with intellectual humility, identifying what I can know and what is beyond my current knowledge must be woven into the entire framework and perspective of my work. It may be pedestrian to simply state, but for myself I needed the reminder in front of me from the beginning, and throughout the work, as I did in my thesis :

Of necessity, portions of the analysis must remain inconclusive; this is not a failure, but merely the nature of such research. Everything cannot be known and recognizing those limitations is part and parcel of this work. With that is the recognition that much can be known, and it is in the tension between what can be known and what cannot be known that I endeavor to present the results of my analysis.6

I decided I would rather err on the side of caution, than fall into arrogance. If I do not habituate this awareness and exercise humility deliberately, then I will not succeed in incorporating it into my work. Key tools of humility, particularly in academic work, are the pedantic citations, references, footnotes, and bibliography. I must be able to support every step of my analysis and show the background and methodologies that support my conclusions. As an exercise in humility, it is an excellent means for forcing me to reckon with what I think I know, and drawing the line at what I do not know. This thread of humility is one of the foundational elements I would weave into all my works.

Values

In the Academy (as it is referred to in such august places as Cambridge University), other priorities often take precedence over humility. Esoteric conversations, unintelligible to any not in the same niche, are the order of the day. The abstract reigns over the practical, the theoretical over the pragmatic. The look of condescension I received upon asking a PhD student to give me a summary of his methodology was brushed over with a laugh: “I’ve not thought about methodology since my undergraduate days!” It is the presumption of youth to leave behind the foundations of their discipline, particularly in these universities where many doctoral students have not yet reached the grand old age of 30. Thankfully, it is not impossible to find a heightened awareness of one’s ability to err or the firm grasp of the essential tools among the tenured and senior scholars. As Dr. Mary Douglas, a prominent anthropologist of the 20th century, noted about her mistakes, “Longevity is a blessing in that it gave me time to discover them.”7

A development in recent decades is the slowly growing awareness of the cost of siloed research (in certain circles, at least). In fields such as medicine and engineering, specialized studies were often a positive, and needed, development (I am thankful my barber is not my dentist). The fruit of specializations has produced information and research far beyond what a generalist could accomplish in her lifetime. But, in the humanities, it has detriments. One professor gave the following example:

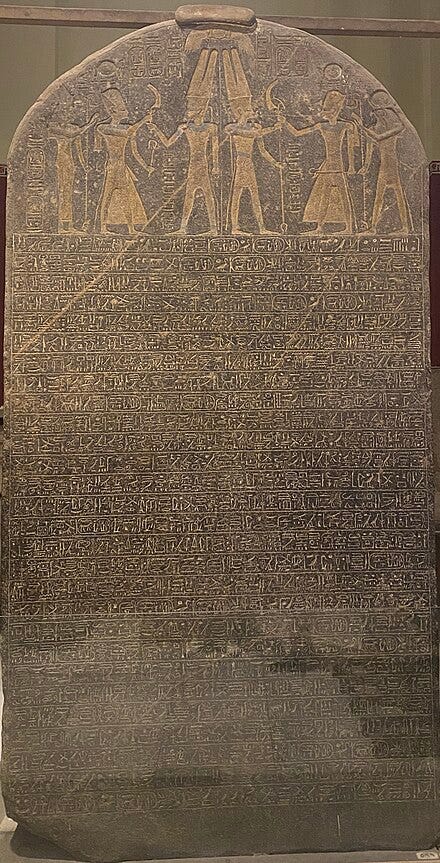

Merneptah Victory Stele8

A stele is discovered in an archaeological dig. The archeologists look at the location and physical context of its finding. The linguists define the phonology, morphology, and syntax. The epigraphers peer at the writing itself. The philologists consider the contemporaneous culture, its history and economics. The historians ponder the content of the text. The art historians elaborate on the symbols. And (more often than not) all these specialists do not consult with each other, nor reference each others’ fields, nor take all the pieces and put them back together. In many cases, they areoblivious of parallel research.9

It may sound ludicrous to those outside the Academy, but I can attest to this phenomena through personal experiences. The cost of such stringent attachment to specialized knowledge may cripple the research; what may stump the scholar in one discipline may be supplemented or even revealed by another, to say the least. In recent years, cross-consulting may be more encouraged (e.g. a biblical studies student drawing on Semitic linguistics), but while leading universities may advertise their prioritisation interdisciplinary research, in practice it has yet to be established.10 An interdisciplinary approach helps to negate the fragmentation of the disciplines and provide a more balanced result, but it is not easy. One of the first challenges is the aforementioned disapproval found in the majority of the academic communities, within the university systems and by the scholars themselves. Another is that, due to the specialization, it takes great time and effort to master the tools of different disciplines.

This raises the question that I have wrestled with for several years now. Why should I fight for an interdisciplinary framework? At the end of a year’s intensive prayer, pondering, research, and consultations, after listening to proponents and opponents, it is more simple than not: my approach is interdisciplinary because my life experiences to date have been invaluable for preparing and training me for this academic chapter. My approach to the field of Hebrew language research is irrevocably shaped by every aspect of my life, ranging from my formal education, professional work, international experience, to my teachers, readings, religious beliefs, communities, and family historicity. The perspective and skills I currently hold are not the sole result of five years’ study for a master’s degree, but the ongoing accumulation of Life in all its diversity and complexities. The narrative of my life, the multitude of threads, inform my work and evidence the value of varied perspectives. Therefore, I will continue to develop an interdisciplinary framework because I believe it is the keystone to carrying out the research before me.

Next

My proposed, developing doctoral research project centers on the nature of the root and form in ancient Hebrew, their relationship to the construction of meaning, and what (if any) ontology is reflected in the very form and structure of the language.11 From one angle, it is clearly a matter of Semitic linguistics.12 In another, it easily fits into biblical studies, or even theology, considering that the corpus is the Hebrew Bible. An alternative may be philosophy, and specifically the philosophy of language. Yet an additional perspective yields anthropology as the field wherein ontology is explored.

In this past season, I explored and pondered the benefits of multiple options and finally concluded that Semitic linguistics and anthropology are the most promising starting point for leaving the future open. I already attained a degree in Bible and Theology, as well as an associates equivalent in Philosophy and Western Civilization. Those are fields I can delve into independently, at this point, as well as consult with scholars in the field. While I have a second undergraduate degree in intercultural studies that touched anthropology, it was merely enough to make me aware of the limits of my knowledge in this area. Retaining Semitic linguistics is necessary, as wrestling with the root and form of Semitics is a technical challenge that will push me far beyond my master’s level engagement. Thus, it is Semitics and anthropology that I believe will offer the best intersection for the research, both in carrying it out and for extending into other fields.

This autumn, I began the one year MRes in Anthropology at the University of St. Andrews (Scotland). During the program, Lord-willing, I will apply for the Global PhD program between St. Andrew’s and the University of Haifa, where I completed my master’s degree. Bridging anthropology in St. Andrew’s and Semitics in Haifa, the West and the Middle East, will, I believe, demand a level of engagement with differing worldviews that can only benefit this particular research project. It will not be a short, nor an easy, journey, but then, a vocation should be an adventure.

If I can, like Tolkien’s Samwise, persevere, remembering that the stories worth telling are the stories where each person had many opportunities to turn back but did not, then I will be satisfied.13 This is the start of a new chapter, or even a book. It is exciting. It is daunting. And often it is overwhelming and demands I choose to be courageous against the fear of uncertainty. How it will develop, I do not know. But, that is precisely the nature of an adventure.

Wisdom begins in wonder.

Tamar

Semitic linguistics is the field of research that studies the Semitic languages. The Semitic language family includes Hebrew, Arabic, Aramaic, Phoenician, etc. Linguistics studies the form and structure of a language (for example, phonology [sounds] and syntax [sentence structure], as well as language discourse—how people actually talk).

Hermeneutic - (noun) a method or theory of interpretation. In other words, the guidelines by which I interpret the text.

Anthropology - (noun) the study of the human condition, their societies and cultures, and their developments. In other words, how a society functions, its spoken and unspoken rules, religious systems, economics, etc., and how it changes over time.

Ontology - (noun) the branch of metaphysics dealing with the nature of being. In other words, it deals with how we perceive the world, i.e. do we have a naturalist ontology, believing in only what can be seen (or proven with empirical science)? Or do we believe in a spiritual (unseen) world too? If so, what is the relationship between the two?

While many have made similar statements, one of the more famous sources is Thomas Hobbes, in his Leviathan (1668), though he took it from Sir Francis Bacon’s “ipsa scientia potestas est” (“Knowledge itself is power”) in Bacon’s Meditationes Sacrae (1597).

Page 12, in Karni, T. 2023. A Linguistic Analysis of the Anthroponyms of the Aramaic Ostraca from Idumea. Haifa: University of Haifa. https://haifa.alma.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/delivery/972HAI_MAIN:HAU/12319960750002791.

Page xvi, in Douglas, M. 2002. Purity and danger: an analysis of concept of pollution and taboo. London: Routledge Classics Edition.

𐰇𐱅𐰚𐰤.

2023. Merneptah Victory Stele exhibited in the Egyptian Museum [Online]. Available from: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0, via Wikimedia Commons. [accessed 31 Octoer 2024]

Cohen, O. 2019. Given in a lecture in the Hebrew Language Department of Haifa University.

Through conversations with professors at such universities, I learned that one august institution will barely consider crossing the lines within the university; working with someone from another university is simply forbidden. In another, they will reluctantly admit to the possibility of interdisciplinary research then revert to emphasizing the need to prioritize one discipline alone. A recent graduate informed me it was heavily frowned upon and not encouraged, no matter what is said by Recruitment. A professor at another European university talked at length of the benefit of interdisciplinary research, but then said, “But you really need to stick to one field, then maybe down the road you can reference other disciplines.”

In a later letter, I’ll share in more detail about how I came to this topic, why I want to research it, as well as what value it could have.

Primarily Hebrew language, but it requires comparative work with other Semitic languages too.

Tolkien, J.R.R. 1954. The Lord of the Rings, The Two Towers, "The Stairs of Cirith Ungol".